C

oherent

signalling

experiments on 137kHz (and

lower) have been taking

place with some good success over

the last few months using

EbNaut

software written by a group of

amateurs determined to push the

weak signalling capabilities of the

bands to the limit.

The

EbNaut

software

[1]

is certainly not plug

and play; it requires that you have an intimate

knowledge of your signal structure, the format

and timing of the message and, for most users,

how to drive

Spectrum Lab

[2]

as well as the

innards and meaning of the terms used in

the driver and receiver software, and that you

agree in advance everything about the message

– except its actual contents, of course! Above

all, you need an accurate frequency source

based on GPS or rubidium locking and timing

on the PC accurate to 100ms. The latter can

usually be achieved with a network time setting

programme such as

rsNTP

[3]

.

How It works

Modulation is binary phase shift keying (BPSK),

but unlike previous amateur use of PSK, the

receiver does not attempt, itself, to recover carrier

or symbol timing. It assumes the transmitting

station is ‘good enough’. Typical symbols

rates used at 137kHz have ranged from 0.25

seconds per symbol to 2s, using messages that

last up to 20 minutes, so the carrier must not

drift by no more than would result in about 45

degrees of phase shift over this Tx period. 45

degrees in 20 minutes at 137kHz requires a

frequency stability of about one part per billion

– no big deal for a GPSDO or rubidium source,

but at the limit for even a good ovenned crystal.

The message is convolutional coded to

add a very high level of error correction. Basic

convolutional coding using two shift registers

(rate½) was described in this column in October

2015 in connection with WSJT. However,

EbNaut

uses eight or more feedback registers

for rate 1/8 or longer coding. It is this extreme

level of added redundancy that allows the

system to get within a dB of the Shannon limit

for some paths. In addition, an outer checksum

is added as a further check of correct decoding

as it is quite normal, and statistically inevitable,

that completely random noise will occasionally

get through the decoding process and generate

garbage messages.

Transmitting

The

EBNaut

encoder is relatively straightforward

to drive. It uses the PC clock for symbol timing,

so this has to be maintained accurately using

a time server or GPS. You specify the sub-

mode (the code rate and level of checksum

strength), the symbol period and the start

time. The symbols are generated and sent to a

transmitter by the simple expedient of toggling

the RTS and DTR lines on a COM port. It is up

to you how you use these to generate a 180°

phase shift; several operators have little more

than a changeover relay and centre tapped

transformer. Others (like myself) have adapted

DDS driver PIC code to reprogram the chip’s

phase shifter in response to an external input.

Others use diode ring mixers. However, note

that using a soundcard and upconversion is not

an option for this mode: as described before,

soundcards are just not good enough.

Receiving

This is where it gets complicated. The

EbNAutRx

software comes in two packages, compiled for

32 or 64 bit Windows (also available in Linux).

If you have a modern machine, use the 64 bit

version to speed the decoding process. It only

works offline, with .WAV files that have been

recorded and saved. Extreme frequency stability

means normal sound card recording is not stable

enough; another solution is needed. The first

thing you have to do is generate a properly timed

(and ideally time stamped) .WAV file of the

received audio. Using

Spectrum Lab

for this was

described briefly in the December Design Notes,

using GPS derived clicks added to the audio to

take out soundcard inaccuracy and drift. Custom

.WAV files with addition of a chunk labelled

‘inf1’ allow arbitrary sample rates, time stamp

and other information to be included. At ‘JNT

Labs, my homebrew 1kHz bandpass sampling

LF receiver (see January’s Design Notes) works

in conjunction with custom PC software to save

compatible low data rate .WAV files.

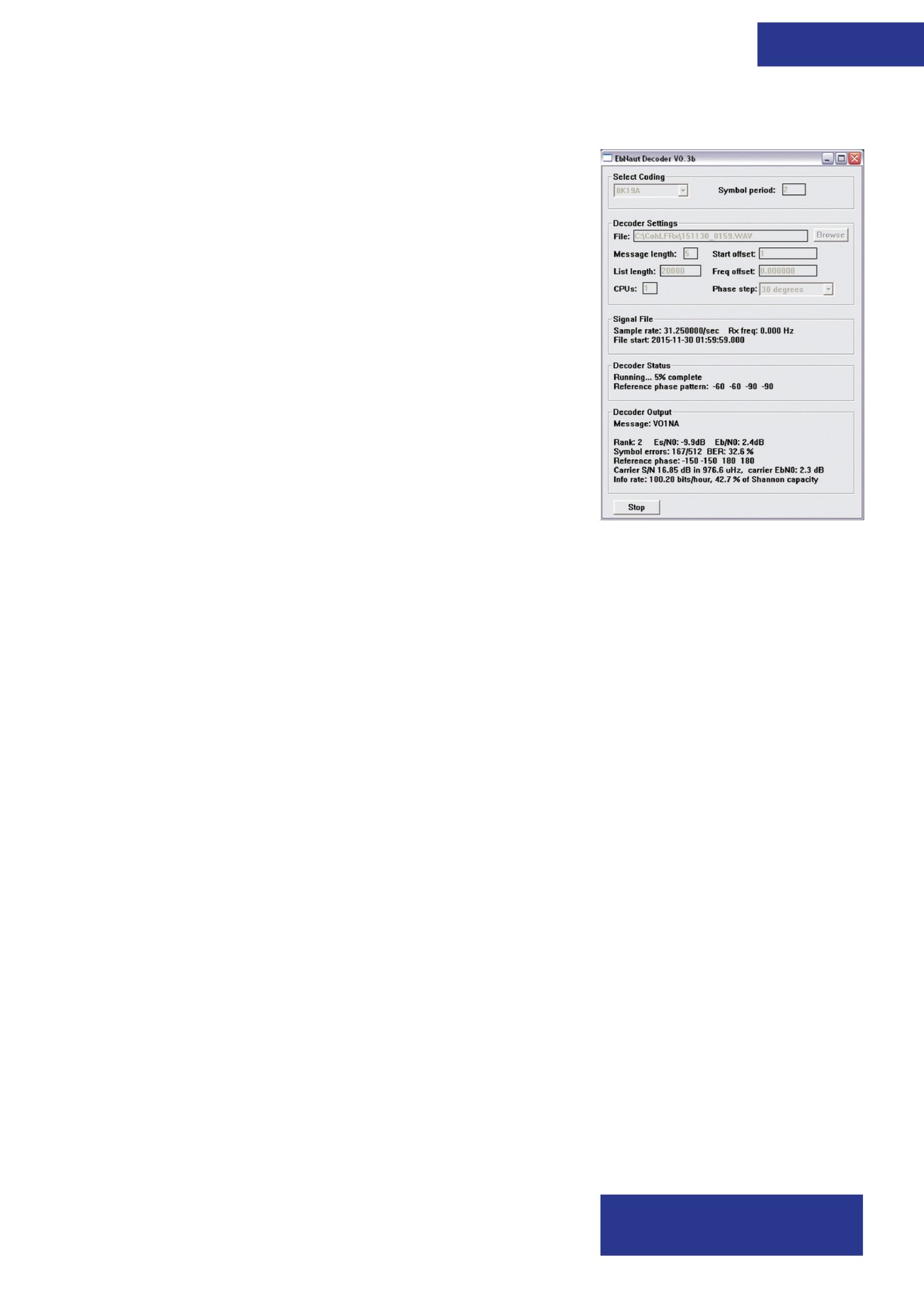

Run

EbNautRx

and browse to find the

recorded file. It is essential that the exact start

time of the recording is known so that any offset,

deliberate or otherwise, can be entered into the

start offset window (my recordings start one

second early by default). The message length,

symbol period and sub-mode are entered and

the decode started. Since the absolute phase

cannot possibly be known in advance, the

decoder has to search over a range of phases to

determine this – you can see it choosing settings

as the software runs. It is doing an enormously

complex computational task, so don’t be

surprised to see the CPU capacity at 100% ! It is

running thousands of Viterbi decoding sessions,

and matching checksums in order to get a valid

one. If you are fortunate, a message will soon

pop up after just a few percent of the overall

progress. Decoding even a short message can

easily take several minutes, so just leave it to get

on with the job. Even after a message appears,

it will go on searching for better solutions. All the

results are stored in an accompanying .TXT file

generated by the decoder.

If there is uncertainty in start times – like the

Tx station is a bit ‘out’ for example – multiple

instances of

EbNautRx

can be started in

parallel, all with identical parameters entered

apart from various offsets in start time. It may

take hours to run, but the chances are, if there

is a message to be decoded it

will

find it!

And finally…

An interesting paper by Pieter-Tjerk de Boer,

PA3FWM entitled ‘Signal/noise ratio of digital

amateur modes’ can be found at

[4]

. This

compares many of the weak signal data modes

we use routinely.

WEBSEARCH

[1]

EbNaut

–

http://abelian.org/ebnaut/The name

EbNaut

derives from the term Eb/No meaning

energy per bit, used as a normalised measure of signal

to noise ratio for digital communications systems.

[2]

Spectrum Lab

audio processing tool –

www.qsl.net/dl4yhf/spectra1.html[3]

Ridiculously Simple NTP Server

–

www.qsl.net/dl4yhf/rsNTP/rsNTP.htm[4] Signal/noise ratio of digital amateur modes –

www.pa3fwm.nl/technotes/tn09b.htmlAndy Talbot, G4JNT

ac.talbot@btinternet.comData

February 2016

27

Regulars

FIGURE 1:

The

EbNaut

receiver screen showing

a successful decode of VO1NA running about

20W on 137kHz.